What patterns do we find when we look to the past of people and things? When we look to the past of people who have lived in the margins, how do we misunderstand their stories? When we look to the past, do we ever consider the importance of things and ideas that are not human? For this paper the emphasis will be to look at the autobiographical American Indian stories of Simon J. Ortiz and Joseph Bruchac. This will be done while trying to contend with several overarching themes, theories and ideas. The attempt will be to pass the American Indian experience, in these particular examples, through modes of thought not typically used in such an endeavor. To begin with we’ll look at Walter Benjamin’s conception of history and the not so obvious problems that arise when we don’t approach history critically. Then, we’ll briefly look at a study done by Susan L. Star and Geoffrey C. Bowker that coincides with Benjamin’s history, where they suggest that residual categories are lost by the wayside in the name of strict organization. Bruno Latour and John Law’s Actor-Network Theory will be the next focus as a unique method in which to reorganize our typical perspective that accounts for non-human agency as much as it considers human agency. This will segue over to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari and their innovative exploration of rhizomes, multiplicity and deterritorialisation. Before all of that, we’ll attempt to draw an outline that takes into account our popular story/narrative/stereotype about the past and present of the American Indian experience. This short paper is an uncharted map that hasn’t been drawn yet. To chart it will be a way to designate what we can know and what our limitations might be. This map will lead us not to a fixed, demarcated destination. It will lead to a series of ideas that will then lead us somewhere else—off the map.

What patterns do we find when we look to the past of people and things? When we look to the past of people who have lived in the margins, how do we misunderstand their stories? When we look to the past, do we ever consider the importance of things and ideas that are not human? For this paper the emphasis will be to look at the autobiographical American Indian stories of Simon J. Ortiz and Joseph Bruchac. This will be done while trying to contend with several overarching themes, theories and ideas. The attempt will be to pass the American Indian experience, in these particular examples, through modes of thought not typically used in such an endeavor. To begin with we’ll look at Walter Benjamin’s conception of history and the not so obvious problems that arise when we don’t approach history critically. Then, we’ll briefly look at a study done by Susan L. Star and Geoffrey C. Bowker that coincides with Benjamin’s history, where they suggest that residual categories are lost by the wayside in the name of strict organization. Bruno Latour and John Law’s Actor-Network Theory will be the next focus as a unique method in which to reorganize our typical perspective that accounts for non-human agency as much as it considers human agency. This will segue over to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari and their innovative exploration of rhizomes, multiplicity and deterritorialisation. Before all of that, we’ll attempt to draw an outline that takes into account our popular story/narrative/stereotype about the past and present of the American Indian experience. This short paper is an uncharted map that hasn’t been drawn yet. To chart it will be a way to designate what we can know and what our limitations might be. This map will lead us not to a fixed, demarcated destination. It will lead to a series of ideas that will then lead us somewhere else—off the map.

We already know part of the story of the American Indians, but let’s review it as we remember it. Their story is an aspect of our American history. It is our story too. Looking back, our memory tells us that the Europeans travelled to the New World to find a new way of life. They were sometimes running from their oppressors in Europe, and once over here, they could invent another way of living. Often they were running away from the people who were telling them how to live their lives. We know that life was hard for these brave colonizing people, the Spaniards, the British, the Dutch, the French, the Germans and the many others. Before this, life was also going along with the pre-colonial hardships for the natives, the Indians, yet with the onset of the Europeans, their sufferings grew exponentially, disease, injustice, war and hatred all coalesced into what we are taught. The Indians were treated unfairly, their land was stripped from them and they were forced into newly oppressive ways of living, thinking and being. The Indians were not Christian and they were not white. Nothing would be the same and nothing can be reversed—the damage has already been done. The regrettable assimilation took some time. Their descendants tell their history, their stories, their myths and legends against the backdrop of the white man’s engulfing narrative. They too are history’s children. In fact, this narrative is a way their stories are told. Everything after this has to take these things into consideration. It is how we understand the American Indian stories now and that past that is gone.

Before we dive headlong into an analysis of American Indian narratives, we should clarify that the above mentioned way of looking at how the stories are understood and mediated, is through our western eyes, our American/Eurocentric perspective. This doesn’t mean, however, that Europeans (and by extension Americans) have always repeated the same tired patterns that got us so confused in the first place. The Europeans we’ll turn for answers in this paper are avid and often subtle critics of the way things are, the way things were, how things have been portrayed, how history has been told, and how to see things from another vantage. For these thinkers, it has been to their benefit to be on the inside of western culture in order to critique it from the outside. We, no matter what ethnicity, need to caution against continuing to make the same hegemonic mistakes of any so-called oppressors, past and present.

The most obvious place to turn our attention, before ANT and the rhizome, is to question the way we understand history, the way history has been told and by whom. The German philosopher, critic, and historian Walter Benjamin is someone to turn to for a unique view of history, particularly with one of his last essays “On the Concept of History” (also known as “Theses on the Philosophy of History”). It’s important to know that this was written around the time Benjamin was fleeing Nazi Germany during World War II, ending up in Spain only to commit suicide in 1940, oddly, same year the essay was written. This is not a random point because it directs us to the notion that Benjamin was critical of the status quo. Historical ideology needs to be called into question directly or indirectly. When we accept things as they are, we suffer for our acquiescence as well. Benjamin was critical of a view of history as truth simply waiting to be discovered. The British sociologist Graeme Gilloch, in his book Walter Benjamin, writes that for Benjamin’s way of thinking about history “…the image of the past becomes a source of, and focus for, contemporary struggle and conflict. What has been is always open to (mis)appropriation and erasure” (225). This is amplified in Benjamin’s essay when he underscores the idea that a history of the vanquished is told by the victors “…not even the dead will be safe from the enemy, if he is victorious. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious” (¶ 6). And later, Benjamin continues with the idea that history is a story told by the victors “the spoils are, as was ever the case, carried along in the triumphal procession. They are known as the cultural heritage” (¶ 7). With any American Indian narrative things are lost, people are forgotten and an Indian’s history is spoken of with condescending pity. Yes, the Europeans took the land, but they can’t exactly give it back either. If blatant misunderstanding thwarts our view of the present moment, then how can we ever imagine the same problems cannot cloud our view of the past, recent and distant? There are plenty of things in the past we’ll never have the ability to summon up. Gilloch quotes Benjamin as saying “the task of history is to grasp the tradition of the oppressed” (226). The trickery of the oppressor always sounds correct under the guise of rational/national progress and in the name of doing good for the sake of others who are less able to so for themselves. However, when doing well entails a dogged insistence on cultural assimilation at any cost, who loses? We often make the careless mistake to demonize people who enforce cultural assimilation, while at the same time stubbornly insisting that everyone follow our line of thinking and if they don’t then they’re in need of improvement because we know better. ‘They are bad, we know better.’ Little do we know, that yes, this sounds innocent, yet if allowed to persist unchecked, it leads to overt oppression and the obliteration of contrary ideas. These long lasting paradigms, unbeknownst to us, are under the surface. To this, Benjamin insists that “The subject of historical cognition is the battling oppressed class itself” (¶ 12). The battling oppressed need to make their voices heard to tell their histories from beyond the blur of stereotypes, myths and rumors. As Gilloch shows, Benjamin’s way of telling history is focused, to a certain degree, fragmentary, which means that a defeated history will “…be only represented as fragments, debris and detritus” (227). This means that in our view of the American Indian context, we can see that there has already been plenty of loss, and this loss cannot be entirely recovered, even with a history that arrogantly aims to be complete. This pattern of history is not what we readily recognize, since we continually want to recover all that has been lost in the mire of nationalism and hatred.

In a 2007 paper by Susan L. Star and Geoffrey C. Bowker, “Enacting Silence: Residual Categories as a Challenge for Ethics, Information Systems and Communication” the emphasis is on showing that in this day and age certain things fall beyond typical categories that are too difficult to classify into neat classifications, resulting in being overlooked, forgotten, or rejected. This idea that we often have a tough time accounting for that which we cannot account for, is similar to Benjamin’s way of doing history, Star and Bowker write “A system without the possibility to understand the history and sociology of its residual categories desiccates stories it already labels ‘unknowable’” (274). The history, people and language that fall outside the normal is easily passed over, thus challenging the normative ways we mis-categorize and ignore what we don’t understand. Even when we dare to think of the English language that American Indian history is usually related as the white man’s lingua-franca, we forget that things are easily lost in the gloss of retelling—in another language. The pattern is now less of a homogeneous past, instead, it is heterogeneous, it becomes tough for us to recognize, and it doesn’t fit all our biased traditions. This heterogeneity will be looked at in more detail later when we compare it to an American Indian narrative to Actor-Network Theory (ANT) and to the rhizome.

Simon Ortiz is an American Indian from the Acoma Pueblo tribe located in New Mexico. He spoke his native Acoma as a child. His story is found in a collection of biographical sketches of various American Indians included in the book I Tell You Now. His autobiographical essay titled “The Language We Know” tells a familiar yet personal story. He opens by giving the reader insight into his relationship with language, how he loves it and how it caused him pain. Ortiz does the difficult job of expressing that he had a love for his native language, while at the same time expressing that he doesn’t speak it much “I had come to know English through forceful acculturation” then, he writes “significantly, it was the Acoma language, which I don’t use enough of today, that inspired me to become a writer” (188). He outlines his history of having to go to an American Indian boarding school where English was the rule, with no room allowed for his culture and, of course, no room allowed for his language. Ortiz addresses this unilateral theme “…I felt an unspoken anxiety and resentment against unseen forces that determined our destiny to be un-Indian” (191). This is a strange and uncomfortable mix of being forced to learn one way in order to better appreciate what you originally had to begin with. It is in this fracture that we anxiously look for what has been lost that might not be found. Benjamin’s oppressive Germany suddenly resonates with how we perceive our own disfigured American past. If we think everyone needs to live life in one way, then we’re not allowing for the possibility of another way of living one’s life. We are often under the illusion that we know this now, after the fact, but do we honestly practice it in our everyday lives?

Actor-network theory (ANT) was developed sometime in the late 1980s by the social scientists Bruno Latour, John Law and Michel Callon. In a paper titled “‘The Social’ and Beyond: Introducing Actor-Network Theory.” The British archaeologist Jim S. Dolwick, is keen to illustrate a primary feature of ANT “Here [with ANT] the definition is significantly extended from humans-only to include anything and everything that might be associated together” (Dolwick, 36). This means that traditional social theory was centered on the human activity and human agency, and rarely, if ever, extended to the non-human activity and non-human agency. For ANT, agency “…is regarded not as a unique human quality or force, which act upon the world, but as an action that is shared with the world” (Dolwick, 38). Every thing, human and otherwise, becomes important when we set out to identify a network. Also, as Dolwick indicates “…ANT places more emphasis on how associations are made…” (36). ANT is less of a theory about networks and more about how networks are connected and associated. ANT, as Dolwick describes it, is also about human and non-human agency. It must be repeated that the non-human things, ideas, entities, organizations, groups, microbes, objects, things, etc. have their influence, affect, pressure, temptation, power on us as much as we have on them, and it is the fluid interconnectedness that ANT wants to bring to our attention. Dolwick underscores this further “…the focus for them [ANT and its proponents] is not on the ‘object’ (in isolation), but on the ambivalent subject-object imbroglio, defined as ‘actor-network’” (38).

We’ll look now to the French philosopher of science Bruno Latour and the British sociologist John Law to define ANT a little more specifically. For Latour an actor-network must not be confused entirely with a standard network of, say an engineering network, a telephone network, etc. As Latour indicates in his essay “a technical network in the engineer’s sense is only one the possible final and stabilized state of an actor-network” (2). So, it is not just a clean-cut technical network that has to be delineated and, as stated with Dolwick, and according to Latour, ANT “…does not limit itself to human actors but [it] extends the word actor—or actant—to non-human, non-individual entities” (2). For our application of how ANT is associated with the American Indian, Latour’s points are easy to see. For instance, with Ortiz, mentioned earlier, his network has to do with his immediate family, his family’s relationship with the land, the land as it is associated with the violence of early colonialism, the land’s inherent value, the current post-colonial concerns of reservation life, his school/s, his farm, how the English language was enforced onto to him, his stories, his parents, the U.S. Government, and all the other connections resulting from an elaborate web of associations that can be thought of as actors in his unique instance. Consider this point and in addition, consider the fact that there can be networks that extend off of all those things, apart from him, as well. When James Bruchac, who was a so-called half breed, writes about his life in “Notes of a Translator’s Son” in the same book of American Indian stories I tell You Now, he asks “do we make ourselves into what we become or is it built into our genes, into a fate spun for us by whatever shapes events?” (199), suddenly we see a possible connection in relation to ANT. It becomes a little easier to answer that it has to be both, his genes and his environment that shape his events, because we can think of events happening in his environment to be his network in action. Bruchac’s network helps create what he is and he helps create what his network is. What is fascinating about this approach is that everything Bruchac and Ortiz detail about their lives, is really an ultra-specific network and all the actors are named. The human actors are obviously named and the non-human actors are also elaborated. For example, with Bruchac’s childhood home “…it is an old house with grey shingles, built by my grandfather…” (199). Ortiz’s family of subsistence farming “…I learned to plant, hoe weeds, irrigate and cultivate corn, chili, pumpkin, beans” (189). These things form a network of relationships and associations, whether we want to call them American Indian networks, spatial networks, or even farming networks that extend way beyond Bruchac’s.

It is easy to sort though some (and only some of) the ways the non-human actors have played a part in the American Indian past, starting with the most obvious contested questions of land, territory, reservations, relocation, and language and so on. These things must be taken into account when we think of their networks, as a matter of fact, these things usually rise to the top of the way we remember the American Indians. Then we must additionally recognize that the American Indian networks can extend far away from these purely obvious things. Let’s not forget that all this also applies to us and that we are not always in control of the relationships and how we are affected by them and how they are affected by us. We are nothing if not in a network.

For another proponent of ANT John Law, in his paper “Actor-Network Theory and Material Semiotics” ANT falls under the “…disparate family of material-semiotic tools, sensibilities and methods of analysis that treat everything in the social worlds as a continually generated effect in the webs relations within which they are located” (2). In this way, the network remains open. The network doesn’t stop making new associations. As for the semiotic approach, the word actor, or actant is important. This is because ANT borrows the definition of an actant from semiotics. In Marcel Danesi’s Encyclopedic Dictionary of Semiotics, Media, and Communications, under the entry for “actant” we find that an actant “…is, in effect, who or what perpetuates or endures specific actions in a narrative” (5). Perhaps due to ANT’s semiotic/linguistic ties, while writing about ANT, Law touches on how translation is related to the network “to translate is to make two words equivalent. But since no two words are equivalent, translation always implies betrayal…” (6), surely, a network includes language and its translation. The way this translation operates works to clarify as much as it distorts and reconfigures. In Bruchac’s aptly titled “Notes of a Translator’s Son” he talks about his avoidance of the calling himself an ‘Indian’ and with a touch of ambivalence he accepts it, but he prefers to call himself a metis “…in English it becomes ‘Translator’s Son.’ It is not an insult, like half-breed. It means that you are able to understand the language of both sides, to help them understand each other” (203). Yes, he writes to us in English and not in his native Abenaki language, and in this, even in translation, we are limited in how much we’ll retain of his actual past. His is a voice that is aware of the limitations of language and this is part of his network—and it is heterogeneous. His network is not always recognizable. We’ve noticed it before, and in this case it is specific, it won’t always look like the predetermined categories we’ve have prescribed for it. Like us, American Indians are creative and they have already learned how to contend with the restraints of history, and so have we, but this doesn’t stop all ignorance. The network of understanding has to remain open, while paradoxically knowing that there will always be closures, obscurities, ignorance and erasures. Ominously, Law tries to sum up ANT by suggesting that “there is nowhere to hide beyond the performativity of the webs” (16). Since we can’t escape, we can at least recognize the patterns that stare at us from the past and that continue to form the future. The networked map of an American Indian past (and present) overlaps with everyone else’s, even if we think it doesn’t.

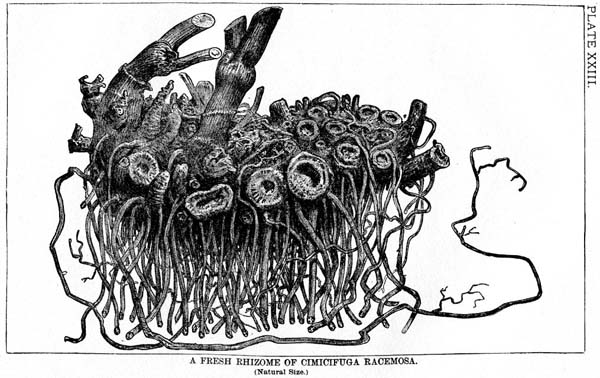

Jim Dolwick helped us to move into the connection between ANT and Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s (D&G) concept of the rhizome. As Dolwick outlines, they have to make the case that the rhizome is against the arboreal (tree-like) ways of thinking and organizing (34). What this means is that Western thinking has consistently clung to the metaphor of a tree, where associations, categories, and meanings are derived from, for instance, the Tree of Knowledge and the like. The botanical metaphor of the rhizome is not like this, since a rhizome lacks the centeredness of a tree’s roots and branches. Dolwick says that the idea of the rhizome “…is depicted as a decentered system of points and lines, which can be connected in any order and without hierarchy” (34). Also, as we’ve noted over and over again, with ANT, D&G’s rhizome takes into account the non-human actors. In D&G’s celebrated book of the 1980s A Thousand Plateaus, the opening chapter takes us right into the concept of the rhizome amidst other complicated permutations of their philosophy. “Multiplicities are rhizomatic…” (8) D&G write, showing that the multiple is not the unified, or arboreal, therefore demonstrating that the rhizome is inherently multiple and multiplying. Interestingly, we find a passage about ants (the insects) “you can never get rid of ants because they form an animal rhizome that can rebound time and again after most of it [the ant colony] has been destroyed” (9). This reflects ANT’s insistence that there is nothing outside a network, and it also emphasizes the persistence of insect connectivity. D&G elaborate and try to summarize what their rhizome is “…unlike trees or their roots, the rhizome connects any point to any other point, and its traits are not necessarily linked to trait of the same nature…” (21). American Indians were not always linked to the Europeans, but now they are, and this rhizomatic pattern is map-able. Remember too, that since we normally come to these things from the arboreal way of thinking, everything has its source, its trace, yet with the rhizome the networks can be tough to recognize. “The rhizome is an acentered nonhierarchical, nonsignifying system without a general and without an organizing memory or central automation” (D&G, 21). In Bruchac’s story, he takes us through his childhood, to a slightly unrecognizable part of it “my junior year of high-school I was still the strange kid who dressed in weird clothes, had no social graces, was picked on by the other boys, scored the highest grades in English and biology, and almost failed Latin and algebra” (198). Here, if we insist on a center, we can find one, but if we don’t, we start to loose the stereotype of this man as an American Indian. His clothes are playing a part in how he’s treated, his emphasis on the different subjects in school he’s interested in, or not, becomes part of his network—another rhizome. It is only when we require that his story needs to be thought of only in one way that we start to lose what D&G wanted to show us with the rhizome. If we can’t let go of a unilateral way of seeing his past, then we’re not seeing his multiplicity and multiplicity as a D&G concept. In an online reference for the term “multiplicity” Nicholas Tampio shows that multiplicity also steers away from the arboreal because “…their [D&G’s] method aims to render political thinking more nuanced and generous toward difference” (1). An American Indian story can always have a unique reading. Their story need not always be about oppression and loss.

Back in A Thousand Plateaus, D&G connect the rhizome to deterritorialisation. “Every rhizome contains line of segmentarity according to which it is stratified, territorialized, organized, signified, attributed, etc., as well as lines of deterritorialisation down which it constantly flees” (D&G, 9). This is fascinating when we are looking at the American Indian with his history with the non-human land itself, the land that was taken (now known as the United States) and the land that replaced their former territory (the reservations). The critical part of what D&G imply is that when there is an established sense of territory, the possibility for that to be disrupted is contained within it, in the form of deterritorialistion. Territory contains it very undoing. Adrian Parr in The Deleuze Dictionary writes on the entry for “Deterritorialisation/Reterritorialisation” where it “…inheres in a territory as a transformative vector; hence, it is tied to the very possibility of change immanent to a given territory” (67). When Ortiz at the end of his essay talks about the continuing of oral traditions of his people, he talks about the obvious barriers “…it is amazing how much of this tradition is ingrained in our contemporary writing, considering the brutal efforts of cultural repression that was not long ago out-right U.S. policy” (194). Here we see this concept of deterritorialisation in its full effect, the process of acculturation deterritorialises the Indians to create a new territory. The Indians have had to reterritorialise their traditions in spite of the efforts to eradicate it.

As we recall any of this history, we remind ourselves of the other histories told alongside this, including our own. We, of course, know of the African Americans who were hated because they were not white, while their work was exploited. We barely remember the way the Spanish (and by extension the Mexican) history in the New World has been maligned and is now forgotten, lost and ignored. When we think of ANT and the rhizome, we should take into account that these are methods to expand our thinking, instead of always trying to narrow people and things down to one or two general stereotypes. However, this should still include the view that everything stems from one source. In other words, we still have to allow for the opposing view, because if we didn’t, we’d have to ignore the very thing that got us in here to begin with and that it is part of the network. American Indians and how their story is told, is generally obscured and misunderstood, as much as they’re never to be reduced to one singular memory since their story is our human and our non-human story—multiplied together—and then some…

Aurelio Madrid

Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter. “On the Concept of History.” The Marxist Internet Archive. Trans. Dennis Redmond, 2005. Web. 11 Nov. 2012.

Bowker, Geoffrey C., and Susan Liegh. “Enacting Silence: Residual Categories as a Challenge for Ethics, Information Systems, and Commincations.” Ethics and Information Technology. 2007. 273-280. PDF. Web. 15 Oct. 2012.

Bruchac, Joseph. “Notes of a Translator’s Son.” Swann and Krupat 195-206.

Danesi, Marcel. “Actant.” Encyclopedic Dictionary of Semiotics, Media, and Communications. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 2000. Print.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1987. Print.

Dolwick, J. S. “‘The Social’ and Beyond: Introducing Actor-Network Theory. Journal of Maritime Archeology, Vol. 4. Springer Science + Business Media. 2009. 21-49. PDF. Web. 15 Oct. 2012.

Gilloch, Graeme. Walter Benjamin: Critical Constellations. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers Inc., 2002. Print.

Latour, B. “On Actor Network Theory. A Few Clarifications Plus More Than a Few Complications.” Soziale Welt, Vol. 47. 1997, 369-81. PDF. Web. 15 Oct. 2012.

Law, J. “Actor Network Theory and Material Semiotics.” Heterogeneities. 2007. 1-21. PDF. Web. 15 Oct. 2012.

Ortiz, Simon. “The Language We Know.” Swann and Krupat 185-194.

Parr, Adrian. ed. “Deterritorialisation/Reterritorialisation.” The Deleuze Dictionary. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2005. 66-69. Print.

Swann, Brian and Arnold Krupat eds. I Tell You Now: Autobiographical Essays by Native American Authors. Lincoln, NE. University of Nebraska Press, 1987. Print.

Tampio, Nicholas. “Multiplicity.” Encyclopedia of Political Theory. 2010. SAGE Publications. PDF. Web. 15 Oct. 2012.

Ah philosophy of history! Something I can talk about slightly well!

I think the myth of the “perfect/complete history” has been pretty thoroughly debunked — the only people I see talking about the possibility of it are determinists (usually cultural). Not to mention the physical impossibility of it (indeterminacy at sub-atomic levels means even the records of particle positions will degenerate over time). But I don’t think that’s quite relevant to what you’re talking about!

When I see the use of re- and de-territorialization, the first thing that comes to my mind is the act-potency exchange in Aristotle. An entity has to have the potential to be something that it turns in to, why an acorn becomes an oak rather than a palm tree, because it only has the potential for the former rather than the latter. The land has these potentials for various uses — symbol, resource, &c — but only when an agent can bring something from potency to act. But generally I think act-potency (and Aristotle in general) has greater explanatory force, for more metaphysical questions, than territorialization.

When I write/read history, I think the greatest burden has to be treating the past as something present, as something with a physical and psychic presence that is not utterly controlled by us. To quote Huizinga (per Lukacs): “The historian . . . must always maintain towards his subject an indeterminist point of view. He must constantly put himself at a point in the past at which the known factors still seem to permit different outcomes. If he speaks of Salamis, then it must be as if the Persians might still win.”

Also, a historian who wrote a brilliant analysis of post-Roman Britain had something to say about Benjamin’s thought of history being written by the victors, that really struck me when I read it earlier this year: http://fpb.livejournal.com/608017.html

“These are the men who, as a rule, write the best history; and their motivation is all too clear. “Let our children know what manner of men their fathers were; and that if we were defeated at last, it was not without honour.” A victor has other things to think about.”

Anyway, I hope you’re well, Aurelio!

– Robert

robert,

thank you for the comment on this paper. when it was submitted, I was in the grip of finals, but finally I’m able to ‘ketchup’ on all the stuff I couldn’t get to right away. I’m interested in your comment for two reasons. one is simply to defend my position that in this paper, I didn’t want to get too in-depth writing about benjamin’s conception of history. the other is to recognize that due to this abbreviation, his position had to suffer any potential misunderstandings, primarily the one you have noted here. again, what is curious is that I thought of the very misinterpretation you highlight—before I posted it. the lesson is that when I have this kind of reluctance in the future, hopefully I’ll have the ability to catch it beforehand & to elaborate as needed.

in these last few days, I’ve been trying to catch up on my reading, all the way from descartes to analytic/formal logic. as for descates’ meditations, I’m paying attention to several points, but one point I have particular fascination with has to do with the fact that before he published the work (sometime in 1647) he had submitted the manuscript to several prominent intellectuals of his day. he must have done this to use their critiques to advance the ideas & to see where he actually ‘got it right.’ as we know, philosophy & ideas work like this, since we need to be as aware as possible to any/all objections before & after the philosophy sees the light of day. the vetting is a refinement. this is not to suggest that the paper had all that much to do with Descartes specifically, although it does demonstrate the value of another opinion &/or point of view.

I thought of going back to the paper to make more adjustments to the Benjamin parts & I probably should, as time permits. I did already make reference to a vital part of what he (benjamin) was doing with the “tradition of the oppressed”, yet I did not carry that over to his marxist overtones & the way this tradition of the oppressed fuses with what I wanted to connect to as far as american indian oppression was concerned. since marxism had so much to do with historical materialism & the use of time in terms of progress, it appears that benjamin wanted to revitalize this exhausted notion (of material progress) to recapture the plight of those whose voices had been lost in the struggles of the past. in our case the american indian’s problems stand as a excellent example with which to reach back into the past to revivify the need to reorganize the way we perceive others who are not white, european, &c. all of this has to be done in the context of now, in other words, this has to be done with full consideration of all that’s been done, all that can’t be recovered, & all that’s been lost. as I see it, benjamin mentions something like a “messianic time” where the ‘sins’ of the past are to be reevaluated & the truth & problems of the oppressed could be a revolutionary departure from the hegemony of imperialism & the like. in other words, we can use the past to inform & power the urge today to give power to those who felt they didn’t have any before, re: the amreican indians.

with any of this said, I would caution substituting any of my interpretation for benjamin’s own words. we still have to have the ability to reinterpret and to have a vigorous conversation about any & all of the ideas mentioned here & beyond. if you have not already done so, I recommend reading benjamin’s theses on the concept of history yourself: http://members.efn.org/~dredmond/ThesesonHistory.html & I also recommend a great little podcast I found by nathan readey that covers the main themes of the theses: https://soundcloud.com/#tobyterrence/walter-benjamins-theses-on-the

aurelio